| NOT AVAILABLE

Giacomo Massa

Rome 1596-post 1635

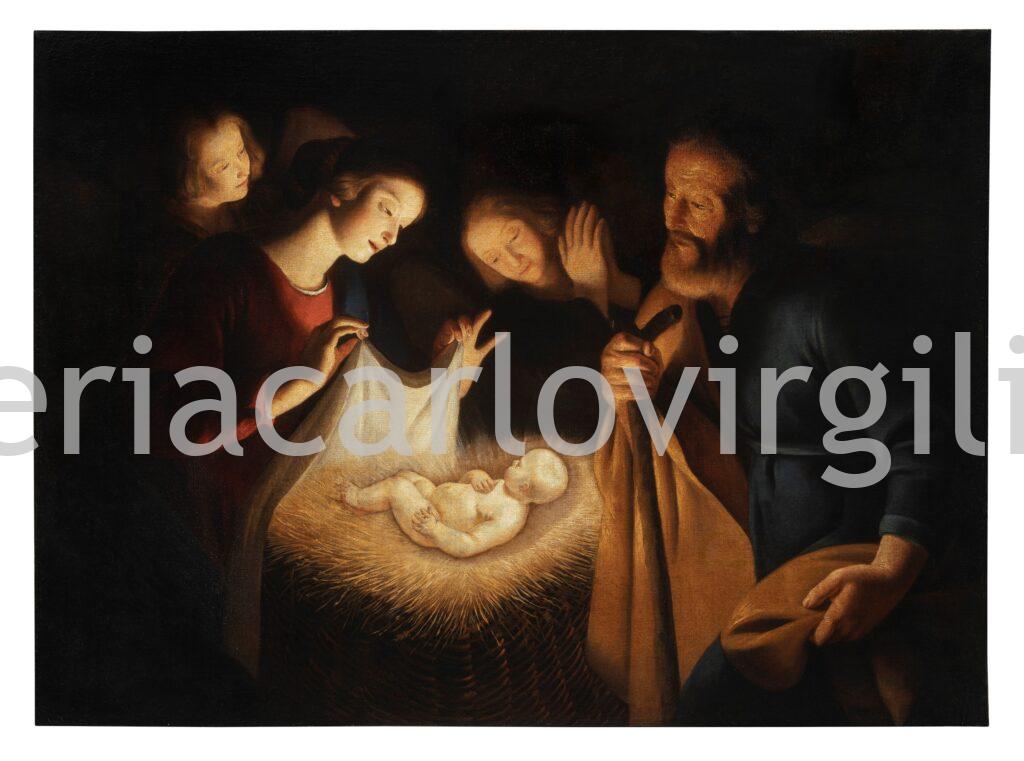

Adoration of the Child •

Oil on canvas 99.2 x 136 cm

The Adoration of the Child, depicted at night, with Mary, Joseph, Jesus in the manger and a pair of angels in the background whose wings can just be made out in the half-light, is the work of Giacomo Massa, the Roman painter whom I have only been able to describe in recent years, along with his cohesive nucleus of canvases, in the past attributed to Trophime Bigot, from Arles and perhaps identifiable with the Teofilo Truffamondo cited in various Roman documents.[1] Before delving into serious questions of attribution it is worth noting the distinctive traits of the artist derived from the triad of altarpieces portraying the Crowning with Thorns, Deposition and Flagellation in the Pizzichetti Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria in Aquiro in Rome, whose documentation, once re-examined, has enabled us to refer the works to his hand with certainty, and to which I will return shortly.

Giacomo Massa, as can be seen clearly in a comparison of the Adoration of the Child under scrutiny with the abovementioned Crowning with Thorns, constructs the features of his faces by simplifying their profiles, which, turned to the light, seem to clearly stand out against the dark background of the setting. The sharp shadows, fruit of the direct observation of nocturnal atmospheres, are useful to show the volumes that appear defined with abrupt tonal passages, not without recourse to red pigment to simulate flushed cheeks and reddened knuckles, in a continual dialogue with the natural. Another of Massa’s stylistic features is painting people with elongated and narrowed eyes – almost as though they were too sensitive to artificial light – obtained by tracing the lash line with a dark brushstroke, merging into one with the iris. Equally, the gestures made simple in order to be intelligible in the dim light embracing the figures was a compositional solution – and at the same time a conscious stylistic signature – appreciated by collectors of the period. Lastly, ideating his scenes, Massa turns them on a luminous central axis, comprised by the artificial source, in our case the figure of Baby Jesus, clearly derived from the prototypes of the Dutch painter Gerrit van Honthorst, whom the artist certainly knew, such as Adoration of the Child at the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence (Inv. 1890 n. 739).

In the Adoration of the Child it is clear how Massa pondered the pictorial successes of Renaissance antecedents, as in so-called Night by Correggio (Dresden, Statens Museum), in which the darkness is lit up not by stars or artificial light sources, such as candles or lamps, but by the Christ Child Himself emanating the divine light. This last is an iconographic solution deriving from an older one where Jesus is portrayed with rays and in the sky to symbolise the comet – as in the Vision of the Magi by Roger van der Weyden in the Bladelin Altarpiece (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) – known in Italy through the woodcuts from Northern Europe. Alongside these cultured figurative references is a pictorial ductus manifestly tinged with Roman reminiscences, oscillating between idealised physiognomies like that of Mary and more rustic ones, as in Joseph, with the swollen hands typical of the old man who has spent his life in humble manual labour, of evident Caravaggesque derivation. While for Jesus sleeping in the manger the artist has quite clearly observed the sculptural prototypes of François Du Quesnoy, at the time spread throughout the collections of Rome, focussed on portraying chubby putti dozing (or quarrelling, or eating grapes), which had a great influence on classicist painters of the calibre of Karel Philips Spierink and Nicolas Poussin.

As stated, as a model for his Adoration of the Child Giacomo Massa seems to have taken a painting of the same subject by Gerrit van Honthorst, to which we can add canvases by Matthias Stom, such as Adoration of the Shepherds from the Museo Civico of Turin and, even more conceptually similar, the versions conserved in Leeds, at Temple Newsam House, and Hull, in the Catherine O’Neill collection (this last catalogued by Benedict Nicolson) where the figures of Mary an are delicately lifting the white cloth with index finger and thumb pressed together, to cover Jesus’s tiny naked body.[2] Although simplifying his compositions, as he does the texture of the clothes almost always painted red, earthy yellow and blue, Massa favours thin layers of pigment, later skilfully raised with touches of the brush in fluid, rich colours; in the Adoration of the Child this can be seen in the straw of the manger, on the tips of Mary’s fingers, on her face and on that of Joseph. Clearly Massa has an ability to merge the languages of various masters and summarize multiple figurative insights, building into the repetition of prototypes such as personal features an ample and continuous artistic production, sufficiently marked and with great atmospheric suggestion in strong chiaroscuri.

In recent decades experts have greatly pondered the theme of the nocturne and candlelight, giving rise to intense critical activity above all regarding a production of canvases in Caravaggesque style of which it was hard to determine the author. Initially they were conveniently grouped under the title of Candlelight Master, then under that of an artist who made a fleeting appearance as the abovementioned Trophime Bigot – to whom, it is useful to note, an Adoration of the Magi is attributed, for the Church of San Marco in Rome, signed Theofilo Trufamon, permeated with mannerist arrangements and a long way from the suffused atmosphere produced by the refractions of artificial light that distinguishes the group of paintings.[3] To complicate the question, in 1978 Jacques Thuillier published a document demonstrating a deposit of thirty scudi paid in 1634 to a certain ‘Mastro Jacomo painter’ for a work for the Chapel of the Passion in Santa Maria in Aquiro later identified as that portraying the Deposition of Christ.[4]

Cross-referencing various documents established a solid basis respecting the identity of the author of the nucleus of paintings distinguished by artificial light. In 2012, I conducted comprehensive archival research and finally found a definitive name, identifying Mastro Jacomo with Giacomo Massa,[5] an increasingly emergent figure. Then in 2020, a study by Rossella Vodret and the late lamented Giorgio Leone established the painter’s Roman origin and his date of baptism in the Parish of San Marco on 26 September 1596. Son of Pietro Massa, originally from Fermo in Le Marche, and Felice Berta from Rome, Giacomo Massa appears under the description “Roman painter” in 1627, when he was liberated from the workshop of a colleague with whom he had carried out an apprenticeship.[6] The young artist was perhaps most influenced by Gerrit van Honthorst, active until 1620 in Rome, where he becomes famous as Gherardo delle Notti for his ability to use the artificial light source in canvases with nocturnal settings. The encounter, if there was one, must have occurred during Massa’s phase of training. To Honthorst’s teaching we must add that of another Dutchman, Matthias Stom, whose signature style paintings lit by artificial sources, even hidden from the viewer’s eye, were particularly prized by the collectors of the time. The possibility that Trophime Bigot had a role in the training of Giacomo Massa must be excluded for the time being, in that the information supplied by Joachim von Sandrart in his Teutsche Akademie according to which the Frenchman painted by candlelight,[7] finds scarce support, among which, besides that of the Giustiniani inventory, one in the unpublished inventory of Marcantonio Vittori from 1627, which recalls «a painting of two people playing a game by night at Truffamondi with black frames» in the Galleria at Monte Cavallo, suggesting the artist’s choice to set genre scenes in dimly lit surroundings, and not holy ones, which, however, make up almost all the numbers in the catalogue compiled by Benedict Nicolson[8]. Today these paintings can be duly attributed to the hand of Giacomo Massa, apart from some canvases that are obviously the work of other artists.

Indeed, to reconstruct the artist’s catalogue, the unavoidable point of departure remains the three altarpieces painted for Santa Maria in Aquiro. The patron, oil producer Francesco Pizzichetti, whose will, drawn up on 25 October 1629 names the guardians of his daughter Cecilia as Francesco Giordano and Luca Tartaglia, and charges them with overseeing the decoration of a chapel in Santa Maria in Traspontina, which underwent a name change by codicil the following day to Santa Maria in Aquiro.[9] A combination of stucco and fresco decorations made by the stucco worker from Como, Giovanni Angelo Bartolo and the painter Giovan Battista Speranza, surround the three large canvases, which have come down to us in varied conditions, depicting the Crowning with Thorns on the left, the Deposition above the altar and Flagellation on the right (Figs. 3-5). Painted «by night light», according to a seventeenth century definition generally reserved for paintings by the founder of the genre, which is to say the abovementioned Gerrit van Honthorst, for a year the three canvases constituted one of the most fascinating Caravaggesque enigmas that, as we have seen, attracted the attention of many experts.[10]

As mentioned, recent research has revealed the artist responsible for the three canvases as Giacomo Massa, paid by the Banco del Monte di Pietà between December 1633 and 25 May 1635 a hundred and eighty scudi. The three canvases differ greatly in their state of conservation, perhaps due to their exposure to the heat of a fire that devastated the church’s main altar in 1845, in which the Visitation of Saint Elizabeth by Carlo Maratta was destroyed,[11] as well as to ambient damp. Restoration carried out by Carlo Giantomassi and Donatella Zari brought to light that the three paintings share supports, canvas with a perpendicular weave, and priming preparation, the same to be found in Adoration of the Child, which therefore suggests a similar date as the Pizzichetti commission, that can be placed in my opinion between 1630 and 1635.[12]

The documentary findings have shed light on the artist, invalidating the hypothesis that Massa only carried out the role of entrepreneur at Santa Maria in Aquiro, as suggested initially by Giorgio Leone,[13] and later by Gianni Papi who, even after the publication of the relevant payments continued to maintain Massa could not have non painted the three canvases at the same time, with no more proof than direct observation, which in his opinion were painted by more than one artist.[14]

Comparison with the paintings at Santa Maria in Aquiro, indisputably attributed to Massa through documentation, has enabled us to reconstruct a first catalogue of Giacomo Massa in which our painting of Adoration of the Child can be seamlessly included given the peculiar features ascribable to his style described above. Massa, besides working at Santa Maria in Aquiro, painted nocturnes illuminated by artificial light, repeating the same faces that can be seen in Christ in Emmaus at Musée Condé, Chantilly, the Capture of Christ at the Musei Civici in Pesaro, in Christ Mocked at the Museo Comunale of Prato and in Saint Francis in Meditation at the Museo Francescano of Rome.[15]

The old man modelling as Joseph in our canvas is the same to pose for the painting in Chantilly dressed in the garb of the pilgrim of Emmaus who, having recognised Christ, raises both hands in sign of stupor.

We find similar features in the Denial of Saint Peter from a private collection in Montville and again in Joseph the carpenter in the Royal Collection at Hampton Court.[16] In this last canvas the features of Jesus, intent on pouring oil from a majolica jug into the lamp used to light up His putative father’s workbench, can be likened to the angel behind Mary who observes the baby sending out rays of celestial light in Adoration of the Child, as well as the young man with short hair carrying out the same action with the same jug in the canvas at Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome.[17] Recourse to the same compositions suggests the artist used cartoons, important iconographic assets for an atelier, to which are added utensils such as the jug with spout and labelled olio that was widespread in central Italy.

As evidence of these compositional dynamics there is a second version of our painting, more cursive in quality, in the collection at the Monastère des Augustines, Hôtel-Dieu, Quebec,[18] where the scene is tinged with more strongly charged colours in a light of warm tones tending to orange, making the cloth held by Mary, instead of a pure white, a straw yellow in colour (Fig. 8).

Adriano Amendola

[1] A. Amendola, La cappella della Passione in Santa Maria in Aquiro: il vero nome di mastro Jacomo, «Bollettino d’arte», 97, 2012, 16, pp. 77-86.

[2] Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe. Second Edition, revised and enlarged by Luisa Vertova, III, Torino 1990, nn. 1510, 1511, 1538.

[3] Vitaliano Tiberia, Un’aggiunta per Teofilo Trufamond, «Bollettino d’arte», 76, 1990, pp. 71-72.

[4] Jacques Thuiller, La Peinture en Provence au XVIIe siècle, Marseille 1978, p. 3, disclosed the payment pointed out to him by Olivier Michel without specifying the archival source. Elena Fumagalli, Pittori Senesi del Seicento e committenza medicea. Nuove date per Francesco Rustici, in «Paragone», 479-481, 1990, pp. 69-82, in particular p. 75, 81-82 note 37, indicated the archival reference of the document and provided the transcription taken from Biblioteca Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana, Pia Casa degli Orfani Santa Maria in Aquiro e SS. Quattro Coronati, tomo 288, ff. 170r-172r, indicating the original in Archivio di Stato di Roma, Trenta Notai Capitolini, ufficio 2, notaio Leonardus Bonannus, vol. 126, ff. 690r-698v. The documents are also discussed by Cecilia Mazzetti di Pietralata, Prima e dopo Caravaggio… cit., p. 207.

[5] A. Amendola, La cappella della Passione in Santa Maria in Aquiro: il vero nome di mastro Jacomo, «Bollettino d’arte», 97, 2012, 16, pp. 77-86.

[6] Rossella Vodret, Giorgio Leone, La cappella della Passione in Santa Maria in Aquiro: per Giacomo Massa pittore romano, in Georges de la Tour. L’Europa della luce, catalogo della mostra (Milano, Palazzo Reale, 7 febbraio – 7 giugno 2020) a cura di Francesca Cappelletti, Thomas Clement Salomon, Milano 2020, pp. 136-137.

[7] Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée, Jean Pierre Cuzin, Trophime Bigot, in I caravaggeschi francesi, catalogo della mostra (Roma, Accademia di Francia, Villa Medici, 15 novembre 1973-20 gennaio 1974), Roma 1974, pp. 9-23, in particolare p. 9.

[8] Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe. Second Edition, revised and enlarged by Luisa Vertova, II, Torino 1990, nn. 831-874.

[9] Cecilia Mazzetti di Pietralata, Prima e dopo Caravaggio. Appunti di ricerca per il contributo nordico, in Caravaggio e l’Europa. L’artista, la storia, la tecnica e la sua eredità, Atti del convegno internazionale di studi a cura di Luigi Spezzaferro, Milano 3-4 febbraio 2006, Cinisello Balsamo (Milano) 2009, pp. 197-213, in particolare pp. 206-207.

[10] In particular, for the Crowning with Thorns, the best conserved of the canvases, besides the name of Gerrit van Honthorst, the conventional Candlelight Master was also put forward, excluding that of Mastro Jacomo, considered simply a follower with stylistic affinities. The discovery of the unknown painter’s name also prompted a review of the corpus of Trophime Bigot, an artist recalled by Joachim von Sandrart as the author of candlelight canvases, and consequently also the Candlelight Master, which are grouped together in Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe. Second Edition, revised and enlarged by Luisa Vertova, I, Torino 1990, pp. 59-64. According to Jean Pierre Cuzin the figure of the Candlelight Master corresponds to Mastro Jacomo of Santa Maria in Aquiro (J.P. Cuzin, Trophime Bigot: A Suggestion, in «The Burlington Magazine», CXXI, 914, 1979, pp. 301-305); for Wolfgang Prohaska, Trophime Bigot is the Candlelight Master, author of the Crowning with Thorns and the Deposition, while Mastro Jacomo is the author of the Flagellation (W. Prohaska, “Il problema”… cit., pp. 99-101; L’enigma Trophime Bigot in I Caravaggeschi. Percorsi e protagonisti, a cura di Alessandro Zuccari, II, Milano 2010, pp. 317-323). Leonard Slatkes, Master Jacomo, Trophime Bigot, and the Candlelight Master, in Continuity, Innovation, and Connoisseurship. Old Master Paintings at the Palmer Museum of Art, exhibition catalogue edited by Mary Jane Harris, Philadelphia 2003, pp. 62-83, recognised the hand of Mastro Jacomo in the Deposition and Crowning with Thorns, excluding that of Trophime Bigot. According to Gianni Papi, Trophime Bigot, the Candlelight Master and Mastro Jacomo are three distinct identities (G. Papi, Trophime Bigot… cit., pp. 12-13). These attributions have been substantially confirmed by Rossella Vodret and Belinda Granata, Non solo Caravaggio, in Roma al Tempo di Caravaggio 1600-1630. Saggi, exhibition catalogue edited by Rossella Vodret, Roma, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia, 16 novembre 2011-5 febbraio 2012, Milano 2012, pp. 85-88.

[11] Erich Schleier, The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine: An Unknown Work of Giovanni Battista Boncori, c. 1673-1675, in the Palmer Museum of Art, in Continuity, Innovation, and Connoisseurship. Old Master Paintings at the Palmer Museum of Art, exhibition catalogue ed. by Mary Jane Harris, Philadelphia 2003, pp. 135-146 in particular p. 142.

[12] See the restoration report in Rossella Vodret, Giorgio Leone, La cappella della Passione in Santa Maria in Aquiro: per Giacomo Massa pittore romano, in Georges de la Tour. L’Europa della luce, exhibition catalogue (Milano, Palazzo Reale, 7 febbraio – 7 giugno 2020) ed. by Francesca Cappelletti and Thomas Clement Salomon, Milano 2020, pp. 135-136.

[13] Giorgio Leone, Mattia Preti a Roma negli anni trenta del Seicento: tracce e riflessioni, in Il Cavalier calabrese. Mattia Preti tra Caravaggio e Luca Giordano, exhibition catalogue (Torino, Venaria Reale, 16 maggio-15 settembre 2013), ed. by Vittorio Sgarbi, Keit Sciberras, Cinisello Balsamo 2013, p. 34, n. 55.

[14] Gianni Papi, Maestro del lume di candela (Giacomo Massa?), in Gherardo delle Notti. Quadri bizzarrissimi e cene allegre, catalogo della mostra (Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi, 10 febbraio-24 maggio 2015), Firenze 2015, p. 246, n. 56.

[15] Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe. Second Edition, revised and enlarged by Luisa Vertova, II, Torino 1990, nn. 833-836, attributed to Bigot. A. Amendola, La cappella della Passione in Santa Maria in Aquiro: il vero nome di mastro Jacomo, «Bollettino d’arte», 97, 2012, 16, p. 84, first to attribute the canvases to Giacomo Massa, an opinion later taken up by Rossella Vodret, Giorgio Leone, La cappella della Passione in Santa Maria in Aquiro: per Giacomo Massa pittore romano, in Georges de la Tour. L’Europa della luce, exhibition catalogue (Milano, Palazzo Reale, 7 febbraio – 7 giugno 2020) a cura di Francesca Cappelletti, Thomas Clement Salomon, Milano 2020, pp. 131-143.

[16] Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe. Second Edition, revised and enlarged by Luisa Vertova, II, Torino 1990, nn. 846, 862.

[17] Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe. Second Edition, revised and enlarged by Luisa Vertova, II, Torino 1990, n, 864.

[18] Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe. Second Edition, revised and enlarged by Luisa Vertova, II, Torino 1990, n. 859.

The Carlo Virgilio & C. Gallery searches for works by Massa Giacomo (1596-post 1635)

To buy or sell works by Massa Giacomo (1596-post 1635) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650