| NOT AVAILABLE

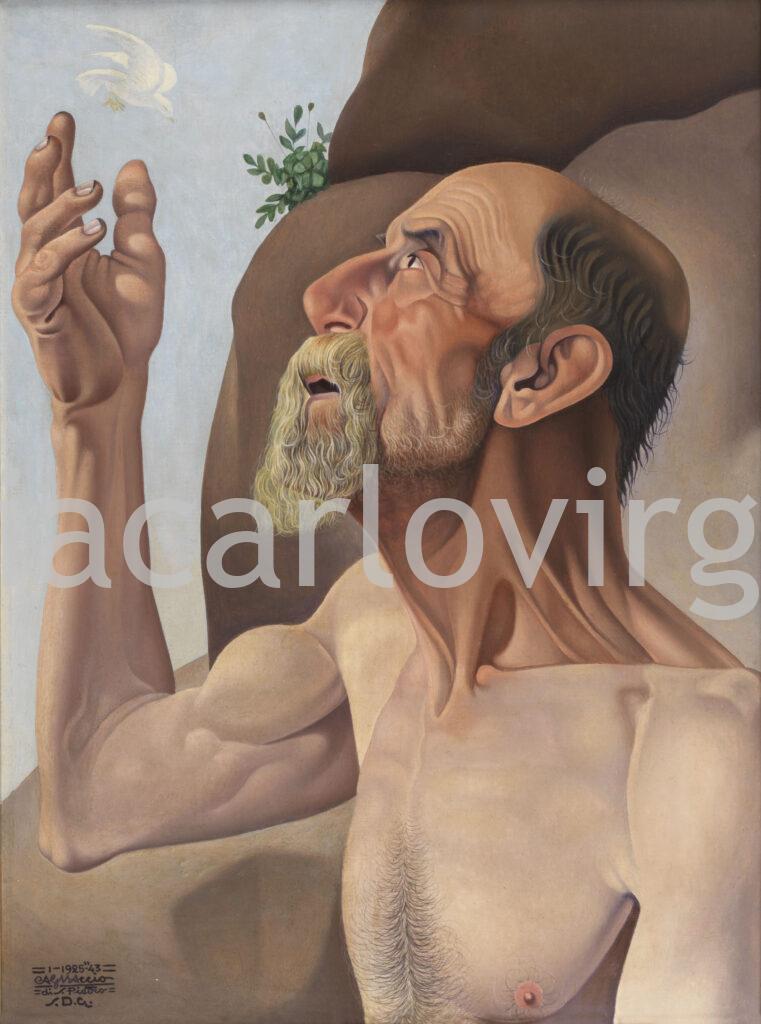

Cagnaccio di San Pietro (Natalino Bentivoglio Scarpa)

Desenzano del Garda, 1897 – Venice, 1946

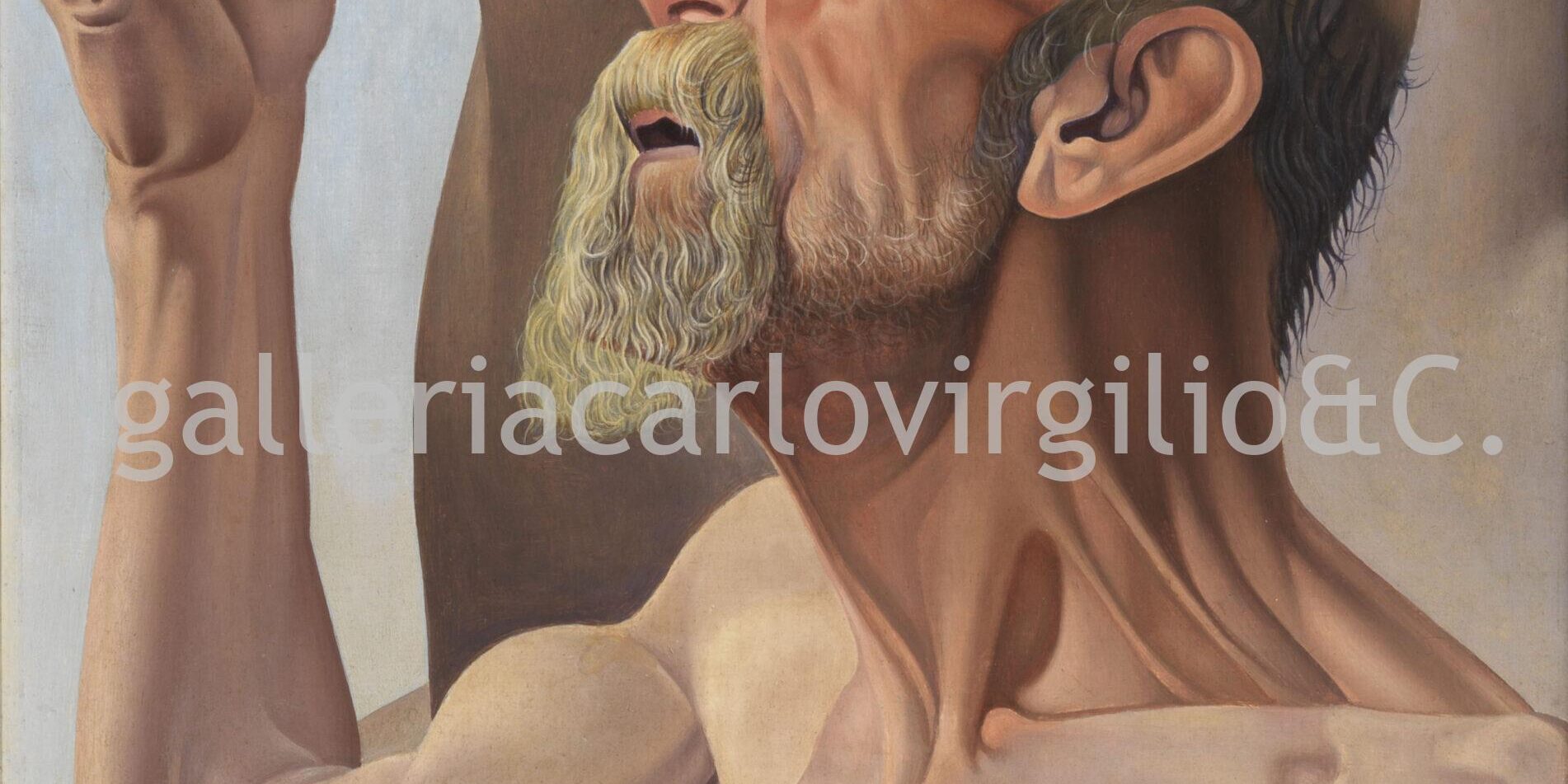

Saint Jerome • 1925-1943

Oil on canvas, 72 x 57 cm

Signed and dated bottom left: = I – 1925”– 43 = / Cagnaccio / = di S. Pietro = / S.D.G.

Bibliography

Mostra dei primi espositori di Ca’ Pesaro (1908-1920), exhibition catalogue (Venezia, 1948),

Ferrari, Venice 1948, sala II, n. 40; L. Bergamo, L’arte di Cagnaccio di San Pietro, in “Il Gazzettino”, 18 November 1935-XIV, p. 6; Prima mostra artisti scomparsi (1913-1963), exhibition catalogue (Milan, Palazzo del Turismo, 12-28 October 1963), edited by Unione Internazionale Vedove d’Artisti, Archeotipografia di Milano, Milan 1963, p. 16, n. 41; Cagnaccio di San Pietro, exhibition catalogue (Milan, Galleria Gian Ferrari, 24 May-22 July 1989), Electa, Milan 1989, p. 77; Cagnaccio di San Pietro, exhibtion catalogue (Venice, Museo Correr), Milan 1991, pp. 32, 33, p. 33 ill.; Cagnaccio di San Pietro. Il richiamo della Nuova Oggettività, exhibition catalogue (Venice, Ca’ Pesaro, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, 6 May-27 September 2015), edited by Dario Biagi, Silvio Fuso, Elisabetta Barisoni, Grafiche Veneziane, Venice 2015, p. 18 ill.

This commission to Cagnaccio di San Pietro came in a climate that once again saw the Church directing attention, albeit moderate, to the problem of artistic production, divided between the need to elaborate a new language and that of maintaining respect for traditional issues, resulting in the institution in 1924 of the Pontifical Central Commission for Sacred Art. In 1925, Cagnaccio was commissioned to paint an altarpiece of Saint Martin and the Beggar for the main altar of the church dedicated to the saint in the small Comune of Salgareda, in the province of Treviso, whose decoration was by an artist in the field of D’Annunzio, Guido Cadorin.

In November 1935, the daily paper, “Il Gazzettino,” published in its columns a painting from the preparatory phase of the altarpiece, showing the detail of the beggar’s face with the title Old Man (clipping conserved at Archivio del ‘900); and almost twenty years later, Cagnaccio took up the work again, transforming the subject into Saint Jerome and introducing some slight compositional changes.

In the initial version of the painting, as per the artist’s typical modus operandi, he was already reflecting on the finitude and crystalline pictorial accuracy so contrary to rapid studio preparation, with every tiny detail carefully thought out so as to come very close indeed to the definitive version for the church in Treviso.

With respect to the first version, the signature and date applied to the lower left (which read 1925 / Cagnaccio) have disappeared, added to which the right arm, which in the studio we intuit is stretched forward as in the altarpiece, is here bent and lowered in order to enter the frame more fully, the beggar’s stick has also disappeared giving place to some rocks also in the background, somewhat livened up by a small tuft of grass and the wedge of blue sky against which the saint’s profile stands out. The process of transforming the old man’s head into Saint Jerome is also recorded in a preparatory drawing coinciding with the work under consideration.

With the title Saint Jerome, the work was exhibited both at the Mostra dei primi espositori di Ca’ Pesaro held in Venice in 1948, where it appeared to belong to the artist’s wife, Romilda, and later at the Milanese Prima mostra artisti scomparsi (1913-1963) in 1963.

Although not entirely devoid of that attention to the faces of dispossessed subjects, the painting more clearly reflects, in the brightness of the chromatic application emphasised by the limpid and analytical light and in the rigorously defined lines, Cagnaccio’s personal re-elaboration of themes and solutions derived from the Quattrocento, as much technical as theoretical, the meditation of which entered a climate of wider research with regard to antiquity whose beginnings can be identified, for example, in the work of Tullio Garbari, in which the insistence on essential drawing with the aim of surpassing impressionist naturalism revealed a study of Masaccio and Beato Angelico and more fully entered the “secessionist” mood of Ca’ Pesaro where he exhibited in two solo shows in 1910 and 1913. If, after the war, Cagnaccio’s first experience at Ca’ Pesaro in 1919 still reflected the last youthful suggestions of a futurist tendency with the works Cromografia musicale and Velocità di linee-forza di un paesaggio, regarding his later meditations on art – “I think I’m managing to pictorially translate the abstract and this leads me to the abstruse […] But as painting is an objective art, quite soon I realised that coming from the subjective it couldn’t communicate to humanity and so, disappointed, I found myself a stray believer in search of God” (from his preface to the solo show at Galleria Genova, Genoa 1935, cit. in Claudia Gian Ferrari edited by), Cagnaccio di San Pietro. Dipinti e disegni dal 1918 al 1945, exhibition catalogue, Milan 1993, p. 70) – was he not perhaps unaware of the climate suggested by the colleague from Trento and critics: “[…] If the charming, devote, round and roseate figures tenderly painted by Gentile da Fabriano or Beato Angelico were painted and exhibited today; the public would go into raptures. […] We have to consider the great endeavour of often caricatured naturalistic research, that he prepared through the spasmodic clutches of the Squarcioneschi, or the brutal anatomical outrages of Andrea del Castagno or the perspective absurdities of Paolo Uccello […] Times have changed and progress is towards the greater sincerity of the ancients” (Gino Fogolari, in “Gazzetta di Venezia”, 23 maggio 1913 cit. in Silvio Branzi, I ribelli di Ca’ Pesaro, Pan Editrice, Milan 1975, pp. 27-28).

In the brief passage of a decade it is once more the shrewder critics who define organically the focus on the antique that will culminate in Lionello Venturi’s essay Il gusto dei primitivi published in 1926, certain recognition anticipating the links and possibilities of development with art from the past, and with the publication in 1927 of the monograph dedicated to Piero della Francesca by Roberto Longhi, published by Valori Plastici, in which the critic definitively sanctioned the opening up towards a humanistic rebirth that “gave the troubled spirit of the intellectual and artistic youth of the day a vision contained in mental rigour as regards shape, spaces and content itself. With the evocation of the new reality, without a doubt, Longhi opened a new world to fantasy” (Alberto Ziveri, cit. in Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco (edited by), Scuola romana, artisti tra le due guerre, exhibition catalogue Rome 1983, Mazzotta, Milan 1983, p. 87).

Icy pictorial exactitude, which unsurprisingly made the artist’s work assimilate that of similar experiences in the Central European area, combines here with the choice of a subject of clearly ancient derivation, revealing both attention to popular themes and a highly personal re-elaboration of the classical, that should not be confused with the search for neoclassical purism that already animated, for example, the coeval solutions of Achille Funi, but fruit of a deeper research and individual re-elaboration that, despite an apparent distance – “It is not possible to speak of a return to the ancient still less comparisons to the pre-Giotteschi, when the past is inside us and all before our eyes” (Gian Ferrari 1993, op. cit., p. 70), wrote Cagnaccio in 1935 – he has his main points of iconographic reference in the Venetians of the Quattrocento, from Andrea Mantegna to Carpaccio, and Carlo Crivelli to Andrea da Murano.

If, with respect to the other works from the mid-twenties – Children Playing, The Letter, The Two Sisters – the religious iconography has limited the perspective boldness in favour of a more canonical composition, the incisiveness of the details and hyperrealist fixity of the figure bathed in cold, sharp light reflect the adhesion to a “magical realism” giving us, thanks to the peremptory realism and psychological accuracy, a portrait of rare robustness and spiritual suggestion.

The addition, beneath the signature, of the initials S.D.G., which appear in Cagnaccio’s works from around 1940, can be interpreted as the phrase Soli Deo Gloria (Glory to God alone), taken from the letter John Calvin sent from Geneva in September 1539 to Cardinal of Carpentras Jacopo Sadoleto, to testify that the correct approach of existence springs from expressing and increasing the glory of the Lord.

Francesco Parisi

The Carlo Virgilio & C. Gallery searches for works by Cagnaccio di San Pietro (Scarpa Natalino) (1897-1946)

To buy or sell works by Cagnaccio di San Pietro (Scarpa Natalino) (1897-1946) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650