| NOT AVAILABLE

(Naples 1852 – 1929)

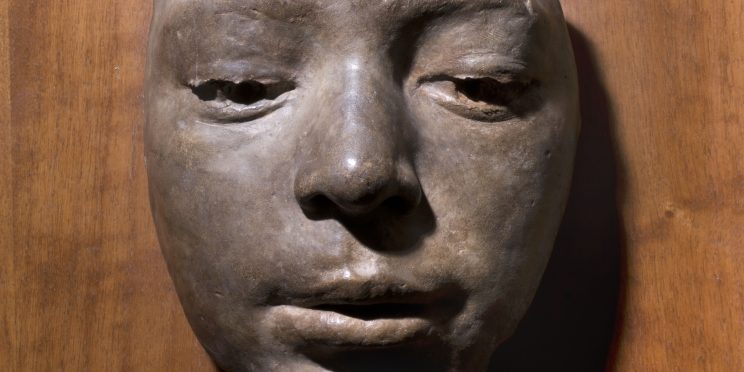

Mask of a Young Lad (Scugnizzo)

1870-72 ca.

terracotta with slipware (ingobbiatura)

The mask is probably the portrait of a young lad, to be attributed to the early work of the sculptor Vincenzo Gemito (1852-1929) and dating to the years between 1870 and 1872.

The work is in terracotta, finished with a thin glaze, got by the application of a clear slip, typical of the Gemito’s production in those years. It bears likeness to a fragment, characterized by jagged and irregular edges, which almost seem to give it the appearance of an archaeological find.

From a stylistic point of view, the sculpture is in line with the numerous portraits of boys and girls created by Gemito between 1870 and 1872, years in which he worked in the cramped rooms of S. Andrea delle Dame in Naples, which was frequented in the same period by other talented young artists, such as Antonio Mancini and Achille D’Orsi[1]. The result of modeling is also similar, symptomatic of the research into the different possibilities of modeling clay and of the effects produced by light on the material engaged in by the artist during that period. In the early seventies, in fact, Gemito developed a very personal technique of working the material: no longer bound by rigid academic dictates, but based on a direct handling of the clay, without the mediation of work tools[2].

This modus operandi is clearly evident on the surface of the mask, as well as in other coeval works such as the Fanciulla Velata and the Ragazzo Moro, both held by the Museo Nazionale di San Martino in Naples. In confirmation of this direct method of working the surfaces bare abundant traces of the artist’s fingers. The sculptor’s thumb seems to have insisted with greater pressure on some areas of the surface, in order to make them rougher and more vibrant. The fingermarks, left visible, convey the light through microscopic grooves and, consequently, generate innumerable minute shadows, similar to small and elusive brushstrokes. On the mask in question, these traces are evident above all on the left side of the nose, at the height of attachment to the eye, and on the left eyelid.

Gemito’s personal technique of sculpture aroused interest and bemusement already among his contemporaries. Of these, one should mention Salvatore Di Giacomo, who, in the biography of the artist published in 1905, reports in great detail the testimony of Stanislao Lista, the sculptor’s teacher. He declared he had seen him working directly with his hands, a method immediately interpreted as strongly innovative – and in some ways anti-academic – that was also to lie at the base of Gemito’s hostility to marble[3].

In addition to the technique involved in its making, the Maschera di fanciullo may be numbered among Gemito’s portraits of the early seventies, also because of its compositional features. In fact, one remarks an analogous vividly pictorial conception of sculpture, evident above all in the expression of the face, characterized by the dramatic play of shadows, concentrated above all in the eye sockets, in the nostrils and in the expedient (recurrent in his sculptures) of the half-gaping mouth.

The piece also shares an intense psychological introspection, underlined by the downturned gaze, and by the position of the head leaning slightly forward. The references are be identified in Hellenistic statuary, loved and studied by Gemito to the point that in 1876 he moved his studio to be close to the Museo Archeologico of Naples[4].

The supposition of there being a close link between the Maschera di fanciullo and the other works dated between 1870 – 1872, such as the Fanciulla velata, the Ragazzo Moro, the Moretto and the Scugnizzo, is further supported by the measurements that, in terms of the area of the face, are compatible. All this would lead one to think that, at some early stage, the work was originally a portrait, perhaps in the round, and that the sculptor transformed it into a mask during its creation, as a fragment may be unearthed by an excavation.

The facial expression brings to mind a Malatiello, a theme dear to the Neapolitan artistic tradition, treated by Gemito as early as 1870 (see the work of that title held by the Museo Nazionale di San Martino, representing a child with downcast eyes and subdued expression).

Unlike the “malatielli” by other sculptors of his time, those of Gemito never present their social condition pathetically to draw the attention of the viewer: on the contrary, they show themselves with naturalness and dignity, with an impenetrable and often dsipassionate gaze on the observer. These characteristics, too, are to be fully remarked in the Maschera di fanciullo, whose gaze emerges from the shadow generated by the half-closed lids hooding the eyes and, above all, by the thick and irregular eyelashes. A similar rendering of eyelashes is characteristic of other works of the same period, including the Giovane pastore degli Abruzzi, held by the Museo di Capodimonte and the famous – but clearly later – Bargello Pescatore. Analogous attention to this detail also appears in the artist’s graphic production, as in the pen and ink drawing on paper known as Il Monello, formerly in the Minozzi collection, now in Capodimonte.

Even the conception of the work as a piece of reality re-emerging in the form of a fragment, similar to the ancient fragments that the sculptor was able to admire on his visits to the Museo Archeologico and the excavations of Pompeii, is not new in Gemito. It is to be found in the lower area of the Ragazzo Moro, as well as in the Fiociniere in the Banco di Napoli Collection, intentionally similar to the shard of an ancient Hellenistic statue, until it reaches the Ritratto di Fortuny, in which the artist dissolves the bounding line between the work and the surrounding environment by means of a jagged and impellent shape. By means of the expedient of the fragment, the sculptor sought to expand his works into space, making them converse with it through the numerous broken and irregular lines that make up their unstable borders.

The theme of the mask – the present one is, in the current state of knowledge of Gemito’s sculpture, the oldest – was to reappear later in the artist’s production, as well as in such graphic studies as the Maschera di Verdi, in works like the Maschera di Gesso in the Minozzi Collection and the small bronze heads of Mathilde Duffaud, one of which is shown on a cushion like a relic, as well as in the self-portrait in raw clay of 1915.

Reference bibliography

S. Di Giacomo, Gemito, in “Corriere di Napoli” 7/8 gennaio 1889

S. Di Giacomo, Vincenzo Gemito. La vita – l’opera, A. Minozzi, Napoli 1905

O. Roux, Infanzia e giovinezza di illustri italiani contemporanei: memorie autobiografiche, Bemporad, Firenze 1909

O. Morisani, La vita di Gemito, Cooperativa Editrice Libraria, Napoli 1936

U. Galletti, Gemito. Disegni, Enrico Damiani, Milano 1944

G. D’Annunzio, In morte di Verdi, Milano 1901

C. Maltese, Storia dell’arte in Italia, 1785 – 1943, Einaudi, Torino 1960

B. Mantura, Temi di Vincenzo Gemito, De Luca, Roma 1989

M. S. De Marinis, Gemito, Japadre, L’Aquila – Roma 1993

D. M. Pagano, Gemito, Electa, Napoli 2009

[1] Morisani, Vita di Gemito, Cooperativa Editrice Libraria, Napoli 1936, p. 33

[2] M. S. De Marinis, Gemito, Japadre, L’Aquila – Roma, 1993, p. 17

[3] S. Di Giacomo, Vincenzo Gemito, la vita – l’opera, A. Minozzi, Napoli 1905, pp. 19 -23

[4] De Marinis, 1993, p. 139

The Carlo Virgilio & C. Gallery searches for works by Gemito Vincenzo (1852-1929)

To buy or sell works by Gemito Vincenzo (1852-1929) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650