| AVAILABLE

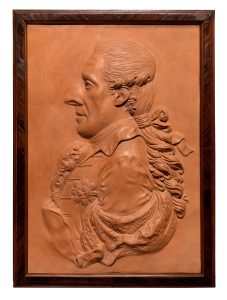

Filippo Tagliolini

Fogliano di Cascia 1745–Naples 1809

Portrait of Sir William Hamilton

1781- 1783

Rectangular terracotta plaque, 43.5 × 30 cm

Coeval frame in veneered wood, probably southern

Provenance: Naples, private collection

Sir William Hamilton, Plenipotentiary Ambassador of His Britannic Majesty to the Kingdom of Naples, is depicted in profile, facing to the left and attired in full dress uniform. Strangely, research undergone for this work revealed that whenever William Hamilton had his profile taken he preferred to turn to the left, according to a tradition immortalised – perhaps for the first time – by Joachim Smith, a modeller at the Josiah and Thomas Wedgwood factory (ill. 1). A cameo in jasper of extreme sophistication and very “British” stylised elegance that portrays the ambassador with a slightly open mouth in the act of speaking in a manner of formal nobility, just as he is depicted in 1776 and 1777 by Sir Joshua Reynolds, but full figure and seated in an official pose in his study surrounded by some pieces from his collection of archaeological vases, with Vesuvius smoking in the background.

It is particularly interesting to begin by drawing a comparison between the plaque by Tagliolini – datable to between 1781 and 1785 – and the small medallion carried out about a decade earlier, in 1772, by Joachim Smith. The two portraits are apparently similar; both show Hamilton in profile turned to the left, they deliberately share details of the hairstyle, are alike in the flourish of the knotted tie at the nape of his neck and the three curls at his temple, identical in tiny details of the cut of the coat, the number of buttonholes, the medal pinned to his chest, the jabot at his neck and the draping of fur that finishes the elegant figure below. And yet how different the man portrayed by Tagliolini. Ten years have passed, Hamilton has put on weight. His neck, no longer slender, rises from a more voluminous chest and his characteristic profile with pronounced nose is drawn without indulgence but to the undoubted advantage of the expression; the lips are now closed with the slight smile of authority and satisfaction of a confident man. The cameo by Smith was carried out in the period in which Hamilton seems to have collaborated a great deal with the Wedgwoods, providing models for the reproductions of Greco-Italic vases that from 1769 were put into production in their Etruria factory in Staffordshire. It is a portrait that seeks to bring out the cultured refinement of the personage and it is not surprising that Smith – like other artists of the same period – had not rendered the full prominence of the nose, which Tagliolini on the contrary, perhaps more intimate and less inclined to pay compliments, had chosen to reproduce by relying on what he saw. A choice, furthermore, previously made in an almost caricatural manner by Dominique Vivant-Denon, again setting out from Smith’s portrait and aiming to provide the maximum expressivity to his sketch by giving the noble ambassador the profile of a bird of prey (ill. 2).

In the case of Tagliolini, nothing is further from his style than to pursue caricature. A moderate artist, he trained in Rome in the difficult moment of transition between baroque and neo-classicism, in his early works carried out for the Real Fabbrica Ferdinandea he still expresses himself, especially in portraiture, in the elegant “Neapolitan barocchetto” in which relief is still given to the movement of drapery but when it came to the facial peculiarities of personages’ likenesses are reproduced with clear veristic reference. For example, in making portraits of the king and queen of Naples, he did not hesitate to produce their realistic profiles, not lacking regality – impressive nose and prognathism in Ferdinand IV, hard expression and obvious undershot jaw in Maria Carolina – reproduced in two splendid plaques in biscuit sent as a gift to Charles III in Spain in 1782 and today conserved at the Royal Palace of Madrid (ill. 3 e 4).

It should be noted that the relationship between Hamilton and the Wedgwoods in the 1860s/70s and the relationship he had with the Director of the Real Fabbrica Ferdinandea della Porcellana, Domenico Venuti, between 1780 and 1790 were diametrically opposite. The Wedgwoods depended on his patronage for their production, needing his consent to reproduce his precious archaeological finds as well as to act as go-between for objects that he found in the antiquities markets of Naples and Rome. It must not be forgotten that Hamilton was the person who bought, besides the fragments of the famous Warwick vase, the Barberini vase that was later sold to the Duchess of Portland, taking her name, and that she is supposed to have lent to the Wedgwoods on Hamilton’s advice. So, the English industrialists must have shown an obsequious recognisance towards Hamilton and felt that a cameo with his portrait would give him pleasure from every point of view. Whereas at the Bourbon factory, it was Hamilton who had to persuade Venuti, who besides being Director of the porcelain factory was also Director General of Excavations in the Kingdom. Thus, Hamilton also needed his indulgence to buy new finds, bypassing the restrictions that prevent the sale of objects found underground, by law the property of the State, except those considered to be less significant or similar to others already present in the royal collections; all at Venuti’s total discretion.

To interpret a work of art is always problematic when various personalities and situations are involved. In our case: the subject, William Hamilton; the artist, Filippo Tagliolini and the Real Fabbrica Ferdinandea.

William Hamilton (1740-1803) arrived in Naples as the plenipotentiary ambassador in 1764 accompanied by his first wife, Catherine Barlow, an heiress of delicate health he had married in 1758, brilliantly resolving the critical financial situation he had as younger son of Lord Archibald Hamilton. He was nonetheless rich in a thorough and cultural education and in his social connections; he was foster brother to George III, King of England, which should not be underestimated. At the time of his appointment Naples was already enjoying the happy situation of being the latest destination on the Grand Tour in the wake of the spectacular archaeological digs launched by Charles of Bourbon and the scientific interest in volcanology due to the intense activity of Vesuvius at the time (1), which happened to be Hamilton’s two great passions alongside music. It is known that when his predecessor James Gray stepped down in Naples giving poor health as his reason when in fact he was afraid of the epidemic with a high death rate that was spreading through the city, Hamilton put himself forward with insistence, like his successor, for a position that was not very popular at the time. Thanks to his prestigious official role, his financial means and his love for antiquities he managed to put together a first large collection of vases that was brought out in print after much trouble in four volumes with comment by d’Hancarville, a true publishing jewel, the Antiquités Etrusques, Grecques et Romaines. It was a publication that would almost become a sale catalogue (2). Hamilton can be said to have been the forefather of the gentleman-merchant, with all the qualities and defects that entails, who not surprisingly ended up spending most of his life in Naples, a transgressive and difficult city, inspiring Francis Haskell to entitle his piece about him as Charlatan or Pioneer?… (3). In the early 1880s, the likely dating for this terracotta plaque, Hamilton was still almost entirely focussed on the hunt for the great archaeological find and research into volcanoes that would also result in an editorial masterpiece, Campi Phlegraei, splendidly illustrated by Pietro Fabris (4). They are the years in which he was visited by Winckelmann, d’Hancarville, Pietro Fabris, Goethe and the most important men of letters and musicians who were passing through Naples. His wife Catherine died in 1782 and Emma Hart – whom he would marry in 1791- only arrived in Naples in 1786. However, the ’90s would be considerably harder years for Hamilton despite the famous Attitudes by Emma and the fact that his collections continued to constitute a mandatory stop for gentlemen passing through Naples; the prestige of his name inevitably being tarnished by Emma’s liaison with Admiral Horatio Nelson becoming public. The catalogue of his second collection illustrated by the sketches of Wilhelm Tischbein – Goethe’s travelling companion in Italy – published in 1795 would not bring the expected economic return following the sinking of the naval ship Colossus heading for England and the loss of the whole collection that had been taken on board with the help of Nelson (5). In 1800, when the French arrived in Naples, Hamilton would leave the city and just two years later he would die in London.

And now for the artist, Filippo Tagliolini. Little is known of his private life preceding his arrival in Naples in 1780 except the details enthusiastically gathered by one of his early admirers, Amerigo Montemaggiori, recorded in the register compiled by Roberto Valeriani and published as a note in the well-known volume by Alvar Gonzàlez-Palacios (6). In a recent study of the porcelain belonging to the Marchese della Sambuca – the minister appointed to the position of Secretary of State in 1776 at the time of Tanucci’s fall into disgrace at the behest of Maria Carolina as being a person welcomed at the court of Vienna where Sambuca had previously had the position of Plenipotentiary Envoy for the King of Naples – it was possible to reconstruct the facts that both the appointment of Venuti as Director of the porcelain factory and the request for Tagliolini to move from Vienna were the direct consequence of the substitution of Tanucci with Sambuca. Sambuca’s appointment represented a clear turning point not only in the modernisation of the royal porcelain factory (Real Fabbrica Ferdinandea della porcellana), his wide-ranging reforms were central to a modern liveability throughout the kingdom, for example the great transformation of the university that not even the Genovese managed to achieve and the launch in 1777 to the creation of the Real Museo Borbonico, the current Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli (7). Hence, it is in 1780 that Tagliolini travels “on loan” from Vienna with the furnace technician Magnus Fessler to give an artistic and technical shake-up to the Neapolitan porcelain factory until then conducted on more or less amateur lines. Tagliolini would never again leave Naples and in complete accord with Venuti would transform the factory’s production – well supported financially by the new administration of Sambuca – into what would be a royal factory, calling card of the kingdom. Given this development, the miniatures that exalted the natural beauty of the Two Sicilies became very important whilst Tagliolini dedicated himself to reproductions of the archaeological heritage of the house of Bourbon and to the official portraits of sovereigns and the kingdom’s illustrious people.

We believe that the terracotta plaque with Hamilton’s portrait could be the prototype for a later version in biscuit that, if it were made, must be supposed to have been among the objects that he took with him when he left Naples. Comparison with the two medallions of the sovereigns leads one to believe that Hamilton’s portrait would also have been shaped in an oval and that in this case the dimensions would have been the same, 43 x 33 cm, using the mould at the factory that had been fine-tuned for the medallions sent to Madrid. It is likely that Tagliolini made a first model in terracotta since we know of at least three other large groups with several figures and a fourth smaller one, all in terracotta: the so-called Montemaggiori group, not coloured and signed by Tagliolini, shown in 1980 by Alvar Gonzàlez-Palacios at the Eighteenth century Neapolitan exhibition (8), the cold painted group at the Museo Correale in Sorrento and the further unpublished work, also cold painted, conserved in a private collection, as is the smaller group. Moreover, our plaque suggests that it would be useful to go further into the role carried out by Hamilton in Naples and find out how close his relations with Venuti as director of Real Fabbrica Ferdinandea actually were. One shouldn’t exclude the possibility that behind the decorative choice of the Etruscan service sent as a gift to George III, King of England, in 1787– with the most interesting pieces of the Bourbon vase collection miniated (9) – was the decisive contribution of Hamilton, in a role not unlike the one he had at Wedgwood, given that if the choice of gift had been left to Ferdinand IV it would certainly have been different.

Angela Caròla-Perrotti

Footnotes

- J. Jenkins – K. Sloan,Vases and Volcanoes: Sir William Hamilton and his Collection, Exhibition Catalogue, London 1996

- AntiquitésEtrusques, Grecques et Romaines, tirée du cabinet de M. Hamilton, envoyé extraordinaire de S.M. Britannique en court de Naples, Napoli 1776-1777, vv. 4 in folio.

- F.Haskell, Ciarlatano o pioniere? Uno storico dell’arte a Napoli nel Settecento, in, Arti e Civiltà del Settecento a Napoli, ed. by C. De Seta, Bari 1982. On Hamilton see also: C. Knight, Hamilton a Napoli. Cultura, svaghi, civiltà di una grande capitale europea, Naples 1990.

- W. Hamilton,Campi Plegraei. Observations on The Volcanos of the Two Sicilies, as they have been communicated to the Royal Society of London by Sir William Hamilton K.B.F.R.S. his Britannic Majesty’s Envoy Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary at the Court of Naples, Naples 1776; a publication to which followed a supplement including a description of the eruption of 1779, Naples 1779.

- Collection of Engravings from Ancient Vases mostly of pure Greek Workmanship discovered in sepulchres in the Kingdom of the TwoSicilies but chiefly in the neighbourhood of Naples during the course of the years 1789 and 1790, now in the possession of Sir William Hamilton, His Britannic Majesty Envoy Extr. and Plenipotentiary at the Court of Naples, with remarks on each vase by the Collector, Naples 1791-95, vv. 4 in folio.

- A.Gonzàlez-Palacios, Lo scultore Filippo Tagliolini e la porcellana di Napoli, Turin 1988.

- A.Caròla-Perrotti, Le porcellane del Marchese della Sambuca, in: Gli amici per Nicola Spinosa, ed. by F. Baldassarie M. Confalone, Rome 2019, pp. 217-229

- A. A.,Civiltà del ‘700 a Napoli 1734 -1799, Florence 1980, p. 154. The group was successively bid for at Christie’s Italy, Rome 24/4/1991, lot 325.

- Fordocuments on the Servizio Etrusco cfr. A. Caròla-Perrotti, La Porcellana della Real Fabbrica Ferdinandea, Cava dei Tirreni 1978, p. 210-212; for the story of the service cfr. A. Caròla Perrotti, ed. by, Le Porcellane dei Borbone di Napoli, Capodimonte e Real Fabbrica Ferdinandea 1743 -1806, exhibition catalogue, Naples 1986, pp. 352 – 375.

For further information, to buy or sell works by Tagliolini Filippo (1745-1809) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650