| AVAILABLE

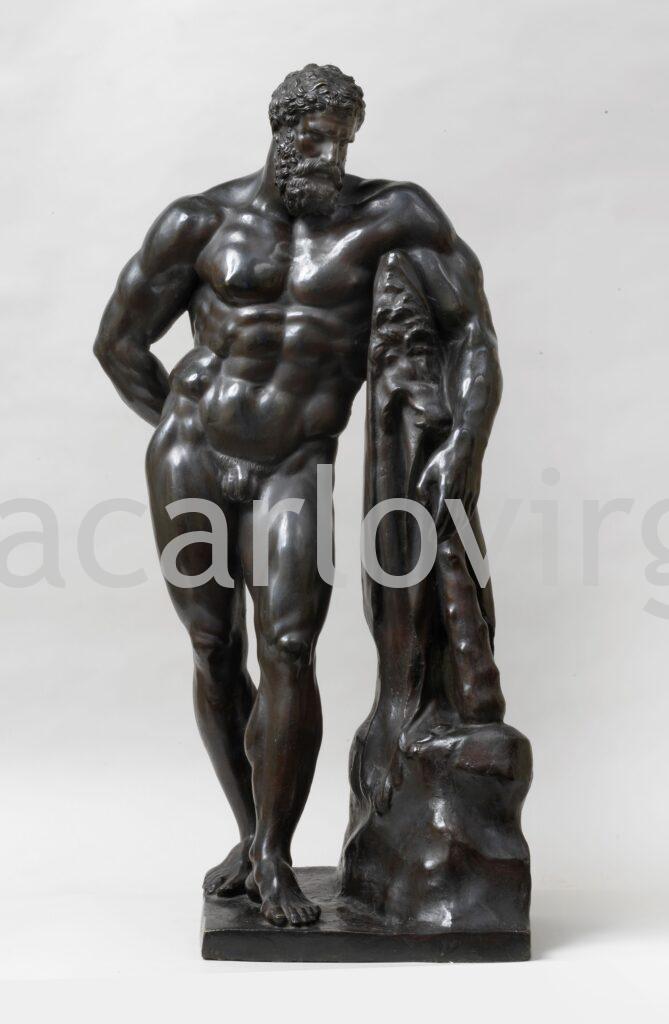

Manuel Olivé (Oliver), model

Active in Rome and Barcellona, documented from 1786 to 1802

Francesco Righetti, bronze cast

Rome 1749-1819

The Farnese Hercules • 1786

Bronze, h 76.5 cm

Signed and dated lower back: “MOlive / 1786”

The Farnese Hercules has held an extraordinary fascination for generations of artist, travellers and collectors, and for eighteenth century theorists it is included in the select group of sculptures ranked as sublime, the highest of the categories attributed to beauty.

Found in 1546 in the excavations of the Baths of Caracalla, by 1556 the sculpture could be seen in the courtyard of Palazzo Farnese in its entirety. In fact when Hercules was originally excavated it was without a head, found years before and immediately replaced, and without the lower parts of the legs, which Michelangelo recommended be substituted by his pupil Guglielmo Della Porta (Haskell, Penny, 1984, pp. 272-280).

The original legs were found some time later, but were not added to the statue because Michelangelo convinced the Farnese family to keep Della Porta’s restoration in order to show that modern sculpture could confidently stand comparison with antique. It wasn’t until 1787 that the sculpture was reintegrated in all its original parts, when the sculptor Carlo Albacini substituted the modern legs with the ancient ones, before the transfer of the famous statue to Naples, where the Farnese collections would be reunited.

There was dismay at the loss of one of the masterpieces that had most contributed to the creation of the unique and inimitable identity of Rome. Goethe experienced the event personally and on 16 January 1787, in his Italienische Reise, he noted: “Rome is threatened by a grave artistic loss: the King of Naples is having the Farnese Hercules moved to his residence. The community of artists is in mourning, although the occasion will permit us to see a work of art unknown to our predecessors” (Goethe, 1993, pp. 178-179). The German writer went on to praise the decision to restore the statue’s original legs, “the aforesaid statue, or better, the part from the head to the knees and the feet with their base, was found on land belonging to the Farnese family; the legs were missing from knee to ankle and Guglielmo della Porta provided substitutes. Until today the statue has stood on these. In the meantime the original legs were found on land belonging to the Borghese family, and could be admired on display at Villa Borghese. Then Prince Borghese made the courageous decision to pay tribute to these precious fragments by giving them to the King of Naples. The alternative legs made by Porta will be removed, and in their place the real ones restored; although to date we have made do with the fakes, we will soon have an entirely new view of the statue and be able to enjoy it more harmoniously” (Ibidem). The debate on the question of the legs had been going on between archaeologists and scholars for some years. Mengs considered inadequate the intervention by Della Porta: “the modern legs that have been applied to it, where the sculptor has carved such hard, tense muscles, don’t seem to be flesh, but cords,” an opinion that in that fateful 1787 was re-published in the new edition of Opere edited by Carlo Fea, (Mengs, 1787, p. 150). In addition, the sculptor Vincenzo Pacetti noted down in his Giornale on 3 May 1787, “I saw the Farnese Hercules with his legs back on, what a wonderful sight” (Pacetti, c 80v).

In this context, the smaller reproduction in bronze of the Farnese Hercules by the Catalan Manuel Olivé the preceding year, in 1786, acquires a highly relevant documentary value, since it is a final witnessing of Hercules before Albacini’s restoration, and brings forward the presence of the young sculptor in Rome by at least two years, compared to the date studies have been able to ascertain until now (Brook, 2017, p. 362). Biographical information about the artist is nonetheless very scarce; in 1784 he is on record at the Escuela del Dibujo in Barcelona entering for a prize, awarded to a colleague rather than him. It is possible that disappointment led him to leave his native city and travel to Rome at his own expense. In September 1788 he won the semester trial of “panni e pieghe” (lit. clothes and pleats) at the Scuola del Nudo in Campidoglio, directed by Andrea Bergondi, with a draped figure in clay, now lost. In June of the following year he entered Pacetti’s studio: “for the last three days a Spaniard has been working here, Don Emanuelle, who comes recommended by Don Francesco Preziado” (Pacetti 2011, c.97r), the director the Spanish grant students who for fifty years had been guiding young Iberians to the Accademia di San Luca and the studios of the most accredited artists. From that moment, the young Olivé learnt a great deal from Pacetti, who oversaw the preparation of the terracotta to be presented at the Concorso Balestra in 1792, promoted by the Accademia di San Luca – Aeneas and Creusa – which won him first prize, revealing the full acquisition of Pacetti’s language in the spiral movement of the two figures draped in billowing, rugged swathes. The work was presented with a patina in faux bronze, of which today there are only slight traces that make the surface patchy (Barberini, 2000, p. 109).

The fact of the bronze patina on the sculpture to be submitted to the prestigious academic competition – a success that also made a name for him at home as demonstrated by the request to Maestro Pacetti from the Barcelona Academy to have a copy in gesso of Aeneas and Creusa – leads us to suppose that in those years the young artist focussed on sculpture in bronze, perhaps within an important establishment such as that of Giacomo and Giovanni Zoffoli, from the 1760s, or of Francesco and Luigi Righetti, which from 1781 specialised in small bronze reproductions of the most famous masterpieces of antiquity to meet the ever-increasing demand for reminders of the grand tour (Teolato, 2010, pp. 233-238).

A copy of the Farnese Hercules is available in the sales catalogues of both firms, and we know that both availed themselves of the help of young external sculptors. So we might imagine that Olivé, having travelled to Rome on his own account, found work in one of these ateliers through Preciado, the director of grant students, most likely that of the Righetti, which, having recently opened, was on the lookout for newly trained and possibly foreign sculptors. Indeed the type of treatment and finish of the surfaces resembles the bronzes from the Righetti studio, as does the size, which, although an unicum, is closer to the productions of Righetti than Zoffoli, because they were not generally larger than a hand and a half in height (Teolato, 2010, pp. 234).

However, an important aspect about this work, besides the very high quality of workmanship, is the date of 1786. As stated earlier, Hercules was an object of debate among connoisseurs, and the restoration of 1787 was warmly welcomed by the art world as a whole. So Olivé’s copy, dating from 1786, although based on the version of Hercules integrated by Della Porta, of which it represents one of the last testimonies, at the same time, introduced a lightening in the proportions of the legs. Olivé had probably seen the originals exhibited at Villa Borghese and so was already imagining the ideal harmony that Hercules would regain due to Albacini’s intervention the following year. Moreover, a certain liberty of interpretation was often found in the realisation of plaster casts, above all in the simplification of the narrative elements and the rendering of surfaces. Olivé’s progress in those years convinced the Junta of the Comercio of Barcelona to finance the young sculptor with a bursary of 12 reals a day, and at his return to Spain in 1796, he was included in the decorative programme of the Junta’s headquarters, Casa Lonja, where the Academy of Fine Arts also had their premises, for which he made the sculptures for one of the façades, with the figure of the founder of Barcelona, Amílcar Barcino, Abundance, linked to commerce, and Carthage, the city that had brought prosperity to the Catalans in the past. In 1802, for the main entrance of the same building, Olivé made the two statues of Africa and America, in which the classicist mould met the desire to confer a certain monumentality to the primitive traits of the personifications of the two continents. From then on the Barcelona Academy began to send its most promising students to Rome, Università delle Arti, to receive the training that each would then develop in their own way once back in their native land.

Carolina Brook

Bibliography:

A. R. Mengs, Opere di Antonio Raffello Mengs, primo pittore del re cattolico Carlo III, pubblicate dal cavaliere Giuseppe Niccola d’Azara e in questa edizione corrette ed aumentate dall’avvocato Carlo Fea, Rome 1787.

F. Haskell, N. Penny, L’antico nella storia del gusto. La seduzione della scultura classica, Turin 1984.

J. W. Goethe, Viaggio in Italia, Milan 1993.

M. G. Barberini, Scheda Manuel Olivé, in Aequa Potestas. Le arti in gara a Roma del Settecento, exh. cat. ed. by A. Cipriani (Roma, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca 2000), Rome 2000.

C. Teolato, Artisti imprenditori: Zoffoli, Righetti, Volpato e la riproduzione dell’antico, in Roma e l’Antico. Realtà e visione nel ‘700, exh. cat. ed. by C. Brook and V. Curzi (Rome, Fondazione Roma Museo 2010-2011), Milan 2010.

V. Pacetti, Roma 1771-1819. I Giornali di Vincenzo Pacetti, Pozzuoli 2011.

C. Brook, Vincenzo Pacetti e gli artisti spagnoli pensionados a Roma, in “Bollettino d’Arte”, Serie VII (2017), volume speciale, pp. 359-364.

For further information, to buy or sell works by RIghetti Francesco (1749-1819) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650